Chicago's Concept-Based Group Exhibitions Show Strength in Numbers

Published on ArtSlant

ASSISTED, Installation view, left to right:Jessica Stockholder, Haim Steinbach, Patrick Chamberlain. Courtesy of Kavi Gupta Gallery

There are forms we know and forms we strive for. This is Plato’s theory—that the ideal is an immovable image, an untouched idea, and that what we know is constantly subject to change and transformation as it goes. For artists and viewers alike, the form of a group exhibition is not always the ideal. The feel of these shows sets up a certain expectation from viewers, often a feeling of decentralization—that the variety of voices is favored over a singular approach, assemblage over inseparability. In a time where installation has been fetishized, and the gimmick of immersive environments has become the norm, we long for the whole, for the perfect oneness of experience.

Many contemporary approaches to conceptual art have become nearly synonymous with vastness, and at times just as romantic, in the sense that the experience of an idea is expected to operate on a scale of largeness, and infinitude. The idea as a landscape. This is another form: this is the solo exhibition.

Since we are speaking of ideals, I recall Pamela Rosenkranz’s widely documented installation for the Swiss Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale. With an expanse of light rose liquid stretching across the entire architecture, the gallery was transformed into a pool, viewable only from a narrow doorway, built with the experience of exclusivity in mind (with space only for a few bodies to experience the principle vantage point at a time). The smell was intoxicatingly synthetic, the very idea of plasticity embodied on the water’s murky surface with every subtle ripple. This was at odds with the delicate and pretty nature of the experience, of the image. The readymade materials— bionin, evian, necrion, neotene, and silicone—were mixed to match the standardized hue of the Northern European skin tone. A sea of downy pastel, like the hue described of one of Nabokov’s nymphette’s bare shoulders. This is the fantasy of whiteness, said Rosenkranz’s installation, this is skin as we dream it.

One material multiplied speaks volumes.

Pamela Rosenkranz at The Swiss Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 2015. Image courtesy of author.

The description of this one work serves only to set up the dilemma of the group exhibition as a format. How can it compete? That we have fallen into the imagistic approach to exhibitions (easily framed, photographed, and shared) makes an environment out of contemporary art that is perhaps even more hostile to ideas expressed through differences in aesthetics.

In Chicago this season, three exhibitions are faring exceptionally well in combating the assumption that the conceptual experience of cohesion need come from homogeneity.

Theory of Forms at Patron Gallery

We start, fittingly, with Theory of Forms, currently on view at Patron Gallery—a new space headed by Emanuel Aguilar and Julia Fischbach, former Directors at Kavi Gupta Gallery. The Platonic nod in the title, while it certainly applies to the work on view—a collection of painting and objects that employ trompe l’oeil, material malapropisms, and other challenges to the paradigm between the shapes works take versus the concepts they propose—is also done on a very basic level of the exhibition itself. Theory of Forms is aware of its status as a group show. Curatorially, it strikes every chord, featuring 11 artists under the broad guise of including work that challenges reality. This of course is a wide field, yet the view of the exhibition remains focused and steady, reaching a balance between quotational references to art history and the optical function of the work. The installation is economical and straightforward, relating small to medium-scale pieces to one another in an airy and buoyant manner that could leave the seasoned viewer wanting for something more extravagant. But this exhibition is a slow burn, and what it lacks in the awe-inspiring multiplicity and grand gesture of an installation such as Rosenkranz’s, it rewards with closer looking. It is well worth the effort.

Theory of Forms, Installation view. Courtesy of Patron Gallery.

One of the first pieces the viewer encounters is a painting of the sea by Daniel G. Baird, a two-sided picture encased in a glass vitrine. The treatment of the surface is photographic, its other face material—covered in a texture of sand. The mechanism of the installation combines the image and the potential experience of the sea to make a whole that is never viewable at once. Here, it stays suspended in separation. As in other works in the exhibition, there are a series of clues within the image or the form that indicate a mediated experience. This is not a space for the singular; the singular no longer exists in an image-based world. In the age of integrated networks, one has to challenge Plato: while we can accept that yes, reality is the shifting entity, constantly changing through perception and context, how different are our ‘ideals’?

Mika Horibuchi, 5 of Hearts, 2015, Oil on linen. Courtesy of Patron Gallery

In the second gallery, a collection of paintings by Mika Horibuchi lines the wall, mirroring the composition of playing cards. Instead of diamonds and hearts there are soft and voluminous snow-white peaches, peaking out from a wall of crisp green leaves, gently rendered to achieve a level of sameness on the surface of the painting. Textually, these paintings are “read,” ushering with them a string of aphorisms whose echoes lightly hum in the viewer’s ears: luck of the draw; painting the roses red; wild card; follow suit; she has it in spades. These words, of course, are fantasies, but serve to underscore the paintings’ otherwise anxious relationship to the concept of tranquility—while the images seem serene and entirely convincing, their form places them in jeopardy. Horibuchi sets us up; our chips are all in, but what are we playing for?

Germination at LVL3

This exhibition is a trademark of LVL3’s program. The gallery frequently organizes group shows, usually featuring two or three artists, paired with a short idiosyncratic title that allows for the casual interrelation between the works on view. In Germination, the chance encounters between the works of Timothy Bergstrom, Heidi Norton, and Derrick Piens benefit from this format. The show tackles the idea that a concept proposed by one work can expand into being in another. The interrelation between Norton’s The Plight and Piens’ The Yield exhibit this balance most perfectly. For Norton, plant forms are confined within the self-contained system of a sculpture, both kept alive and oppressed by the structure’s form. The Plight both occupies the wall and protrudes from it—coils of bamboo suspended within the frame against the wall echo in the forms of the plastic tubing that spiral around the piece, filled with a translucent, colored liquid that fades from pastels of pink and yellow to neon orange. The colors are reminiscent of pre-mixed hues: detergents, auto transmission fluids. There is something distinctly industrial about them. The sculpture is attempting to keep the plants alive, though we know the lifespan can only be drawn out for so long in their condition. The cessation is imposed, yet aesthetics fight against it. A similar double register is struck for Piens—the term yield flipping between harvesting/production, and hesitation/acquiescence. This text play affects the sculpture, fitting its stops and starts, an object sprouting into form while simultaneously growing against itself. The dilemma proposed in both pieces reaches a similar conclusion, tthrough different means: “natural” production in the studio is a myth.

Heidi Norton, The Plight (feeding Systems), 2015, Acrylic, dielectric glass, resin, vinyl, bamboo, tubing, electrodes with thermal switch,

burner screen, pulley, crystal soil water beads, U- shaped draying tubes, aluminum frame, LCD screens, ball bearings

There is also a sense of tame psychedelia that pervades in all three artists’ works, from Bergstrom’s small formalist paintings that use text as a compositional device—a blue and white canvas that spells Bad Trip, abstractly scrawled across the canvas—to Norton’s An Altered State, where peyote and poppies are pressed between sheets of glass and fired, installed on the wall. In Germination, the hallucinogenic experience is an unattainable one; you can look but can’t feel.

Lucidity is overrated.

ASSISTED at Kavi Gupta Gallery

Curated by and including work of artist Jessica Stockholder, whose exhibition Door Hinges is concurrently on view in the lower galleries of Kavi Gupta’s Elizabeth Street location, ASSISTED features 16 artists, and could easily be a visual essay on form and object-hood. Here, the group exhibition format is approached as a work in and of itself, with all of the included pieces echoing Stockholder’s idiosyncratic method, and in many cases approximating her work.

The viewer’s sightlines are taken into consideration more than in most group exhibitions—every position, angle, and vantage point is transformed into a vista that makes a singular installation out of multiple artists. The primary clinch of this achievement is Stockholder’s sensibility, which permeates all of the chosen works and follows a set of necessary prescriptions: the form must in some way be related to the readymade; the formal palette of the work must be intentional (either works are steadfastly the natural color of the material, or the artists’ chosen colors directly relate to the concept of the piece); and above all the approach must be inventive, but avoid novelty. These rules are immediately obvious. So is the objects’ expected relationship to painting. The sort of self-aware originality in all the artworks intersects with and overwrites itself. As with Stockholder’s aesthetics, this is originality on overdrive—and the exhibition revels in the cacophony.

ASSISTED guides us along the tightrope between the expected and the divergent.

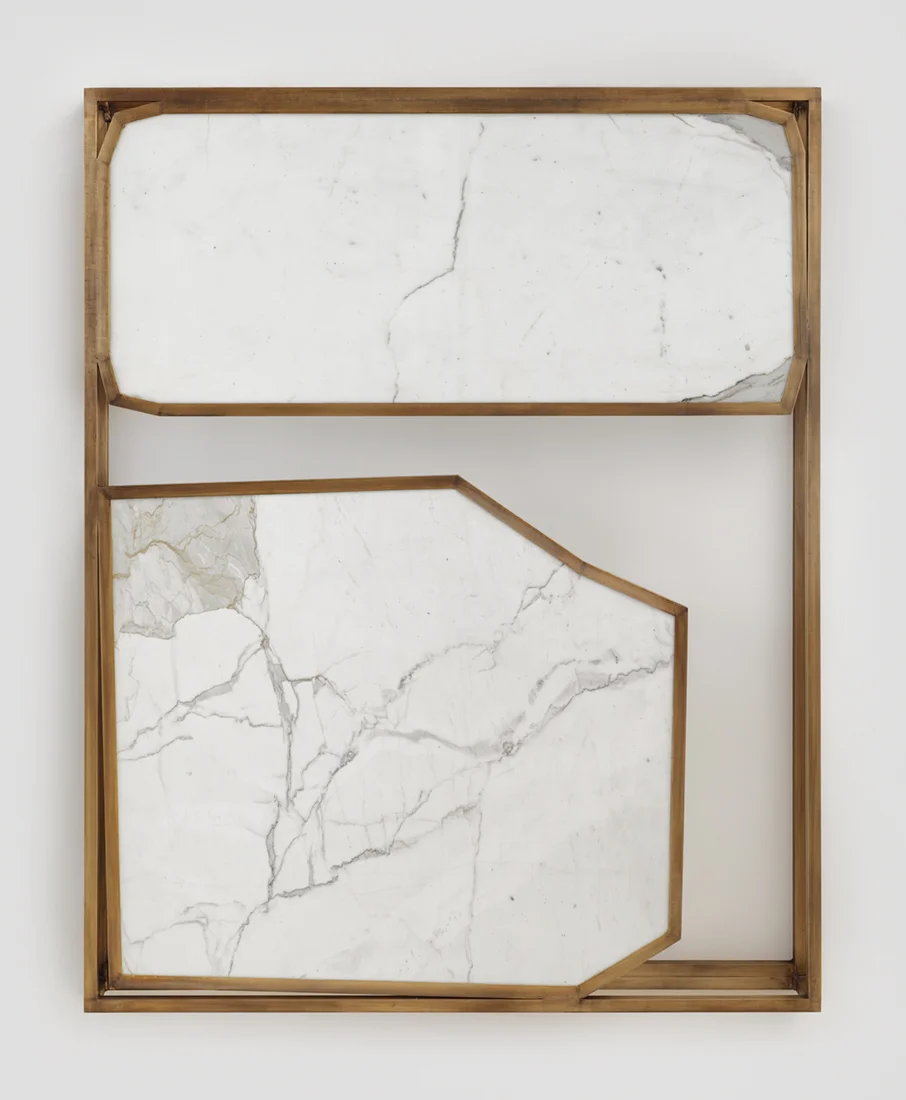

Sam Moyer Marshall Field's 2015 Bronze and marble, 70 x 56 x 6". Courtesy of the artist and Kavi Gupta Gallery

We are first met with Sam Moyer’s Marshall Field’s, a bronze and marble “painting” whose subtle curves describe a geometric composition through the presence and absence of the material. The title, whose name references the Chicago department store before it became Macy’s, allows the viewer to consider the work’s set-design qualities. Though the piece hangs on the wall, it could just as easily occupy a store window. It claims both territories. This same awareness, we could even call it “duplicity,” is upfront in Haim Steinbach’s installation of either and or—two pieces (necessarily separate, as one word is painted on a canvas, and the other directly onto the wall). The statement: painting is both, and installation is itself. The privilege of painting, in Stockholder’s framework, is that its terms are loose and easily exploitable. That Jo Nigoghossian’s Dragon—a metal and neon scribble in space—and Polly Apfelbaum’s City Lights—a painted and embellished carpet—can be viewed in the same proximity is a refreshing challenge to the influx of most contemporary abstraction.

The idea of environment is incredibly important to this show, perhaps more so than the singular landscape (the wholeness of environment) created in pieces such as Rosenkranz’s Venice installation—but of course, the form of the pavilion/solo exhibition lends itself to that approach. What the group lends to Stockholder, as an artist, is also offered to the viewer.

As in Theory of Forms, Germination, and ASSISTED, each imagines its own ideal.